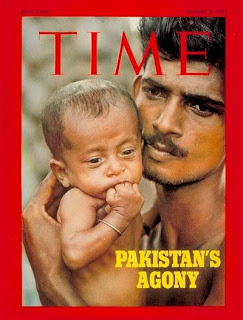

OVER the rivers and down the highways and along countless jungle paths, the population of East Pakistan continues to hemorrhage into India: an endless unorganized flow of refugees with a few tin kettles, cardboard boxes and ragged clothes piled on their heads, carrying their sick children and their old. They pad along barefooted, with the mud sucking at their heels in the wet parts. They are silent, except for a child whimpering now and then, but their faces tell the story. Many are sick and covered with sores. Others have cholera, and when they die by the roadside there is no one to bury them. The Hindus, when they can, put a hot coal in the mouths of their dead or singe the body in lieu of cremation. The dogs, the vultures and the crows do the rest. As the refugees pass the rotting corpses, some put pieces of cloth over their noses.

The column pushing into India never ends, day or night. It has been four months since civil war broke out between East and West Pakistan, and the refugees still pour in. No one can count them precisely, but Indian officials, by projecting camp registrations, calculate that they come at the rate of 50,000 a day. Last week the estimated total passed the 7,500,000 mark. Should widespread famine hit East Pakistan, as now seems likely, India fears that the number may double before the exodus ends.

Hundreds of thousands of these are still wandering about the countryside without food and shelter. Near the border, some have taken over schools to sleep in; others stay with villagers or sleep out in the fields and under the trees. Most are shepherded into refugee camps where they are given ration cards for food and housed in makeshift sheds of bamboo covered with thatched or plastic roofing. Though no one is actually starving in the camps, food is in short supply, particularly powdered milk and baby food.

No More Tears

Life has been made even more miserable for the refugees by the monsoon rains, that have turned many camps into muddy lagoons. Reports Dr. Mathis Bromberger, a German physician working at a camp outside Calcutta: "There were thousands of people standing out in the open here all night in the rain. Women with babies in their arms. They could not lie down because the water came up to their knees in places. There was not enough shelter, and in the morning there were always many sick and dying of pneumonia. We could not get our serious cholera cases to the hospital. And there was no one to take away the dead. They just lay around on the ground or in the water." High-pressure syringes have speeded vaccination and reduced the cholera threat, but camp health officials have already counted about 5,000 dead, and an estimated 35,000 have been stricken by the convulsive vomiting and diarrhea that accompany the disease. Now officials fear that pneumonia, diphtheria and tuberculosis will also begin to exact a toll among the weakened ref ugees. Says one doctor: "The people are not even crying any more."

Perhaps because what they flee from is even worse. Each has his own horror story of rape, murder or other atrocity committed by the Pakistani army in its effort to crush the Bengali independence movement. One couple tells how soldiers took their two grown sons outside the house, bayoneted them in the stomach and refused to allow anyone to go near the bleeding boys, who died hours later. Another woman says that when the soldiers came to her door, she hid her children in her bed; but seeing them beneath the blanket, the soldiers opened fire, killing two and wounding another. According to one report from the Press Trust of India (P.T.I.), 50 refugees recently fled into a jute field near the Indian border when they heard a Pakistani army patrol approaching. "Suddenly a six-month-old child in its mother's lap started crying," said the P.T.I, report. "Failing to make the child silent and apprehending that the refugees might be attacked, the woman throttled the infant to death."

Cordon of Fire

The evidence of the bloodbath is all over East Pakistan. Whole sections of cities lie in ruins from shelling and aerial attacks. In Khalishpur, the northern suburb of Khulna, naked children and haggard women scavenge the rubble where their homes and shops once stood. Stretches of Chittagong's Hizari Lane and Maulana Sowkat Ali Road have been wiped out. The central bazaar in Jessore is reduced to twisted masses of corrugated tin and shattered walls. Kushtia, a city of 40,000, now looks, as a World Bank team reported, "like the morning after a nuclear attack." In Dacca, where soldiers set sections of the Old City ablaze with flamethrowers and then machine-gunned thousands as they tried to escape the cordon of fire, nearly 25 blocks have been bulldozed clear, leaving open areas set incongruously amid jam-packed slums. For the benefit of foreign visitors, the army has patched up many shell holes in the walls of Dacca University, where hundreds of students were killed. But many signs remain. The tank-blasted Rajabagh Police Barracks, where nearly 1,000 surrounded Bengali cops fought to the last, is still in ruins.

Millions of acres have been abandoned. Much of the vital jute export crop, due for harvest now, lies rotting in the fields; little of that already harvested is able to reach the mills. Only a small part of this year's tea crop is salvageable. More than 300,000 tons of imported grain sits in the clogged ports of Chittagong and Chalna. Food markets are still operating in Dacca and other cities, but rice prices have risen 20% in four months.

Fear and deep sullen hatred are everywhere evident among Bengalis. Few will talk to reporters in public, but letters telling of atrocities and destroyed villages are stuck in journalists' mailboxes at Dacca's Hotel Intercontinental. In the privacy of his home one night, a senior Bengali bureaucrat declared: "This will be a bitter, protracted struggle, maybe worse than Viet Nam. But we will win in the end."

Estimates of the death toll in the army crackdown range from 200,000 all the way up to a million. The lower figure is more widely accepted, but the number may never be known. For one thing, countless corpses have been dumped in rivers, wells and mass graves. For another, statistics from East Pakistan are even more unreliable than statistics from most other places (see TIME Essay). That is inevitable in a place where, before the refugee exodus began, 78 million people, 80% of them illiterate, were packed into an area no larger than Florida.

Harsh Reprisals

The Hindus, who account for three-fourths of the refugees and a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of the Moslem military's hatred. Even now, Moslem soldiers in East Pakistan will snatch away a man's lungi (sarong) to see if he is circumcised, obligatory for Moslems; if he is not, it usually means death. Others are simply rounded up and shot. Commented one high U.S. official last week: "It is the most incredible, calculated thing since the days of the Nazis in Poland."

In recent weeks, resistance has steadily mounted. The army response has been a pattern of harsh reprisals for guerrilla hit-and-run forays, sabotage and assassination of collaborators. But the Mukti Bahini, the Bengali liberation forces, have blasted hundreds of bridges and culverts, paralyzing road and rail traffic. The main thrust of the guerrilla movement is coming from across the Indian border, where the Bangla Desh (Bengal Nation) provisional government has undertaken a massive recruitment and training program. Pakistani President Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan last week charged that there were 24 such camps within India, and Indians no longer even bother to deny the fact that locals and some border units are giving assistance to the rebels.

Half of the Mukti Bahini's reported 50,000 fighters come from the East Bengal Regiment, the paramilitary East Bengal Rifles, and the Bengali police, who defected in the early days of the fighting. Young recruits, many of them students, are being trained to blend in with the peasants, who feed them, and serve as lookouts, scouts and hit-and-run saboteurs. Twice the guerrillas have knocked out power in Dacca, and they have kept the Dacca-Chittagong railway line severed for weeks. Wherever possible they raise the green, red and gold Bangla Desh flag. They claim to have killed 25,000 Pakistani troops, though the figure may well be closer to 2,500 plus 10,000 wounded (according to a reliable Western estimate). Resistance fighters already control the countryside at night and much of it in the daytime.

Only time and the test of fire will show whether or not the Mukti Bahini's leaders can forge them into a disciplined guerrilla force. The present commander in chief is a retired colonel named A.G. Osmani, a member of the East Pakistani Awami League. But many feel that before the conflict is over, the present moderate leadership will give way to more radical men. So far the conflict is nonideological. But that could change. "If the democracies do not put pressure on the Pakistanis to resolve this question in the near future," says a Bangla Desh official, "I fear for the consequences. If the fight for liberation is prolonged too long, the democratic elements will be eliminated and the Communists will prevail. Up till now the Communists do not have a strong position. But if we fail to deliver the goods to our people, they will sweep us away."

By no means have all the reprisals been the work of the army. Bengalis also massacred some 500 suspected collaborators, such as members of the right-wing religious Jammat-e-Islami and other minor parties. The Biharis, non-Bengali Moslems who fled from India to Pakistan after partition in 1947, were favorite—and sometimes innocent—targets. Suspected sympathizers have been hacked to death in their beds or even beheaded by guerrillas as a warning to other villagers. More ominous is the growing confrontation along the porous 1,300-mile border, where many of the Pakistani army's 70,000 troops are trying to seal off raids by rebels based in India. With Indian jawans facing them on the other side, a stray shot could start a new Indo-Pakistani war—and one on a much more devastating scale than their 17-day clash over Kashmir in 1965.

Embroiled in a developing if still disorganized guerrilla war, Pakistan faces ever bleaker prospects as the conflict spreads. By now, in fact, chances of ever recovering voluntary national unity seem nil. But to Yahya Khan and the other tough West Pakistani generals who rule the world's fifth largest nation, an East-West parting is out of the question. For the sake of Pakistan's unity, Yahya declared last month, "no sacrifice is too great." The unity he envisions, however, might well leave East Pakistan a cringing colony. In an effort to stamp out Bengali culture, even street names are being changed. Shankari Bazar Road in Dacca is now called Tikka Khan Road after the hard-as-nails commander who now rules East Pakistan under martial law.

Honeyed Smile

The proud Bengalis are unlikely to give in. A warm and friendly but volatile people whose twin passions are politics and poetry, they have nurtured a gentle and distinctive culture of their own. Conversation—adda—is the favorite pastime, and it is carried on endlessly under the banyan trees in the villages or in the coffeehouses of Dacca.

Typically, Bangla Desh chose as its national anthem not a revolutionary song but a poem by the Nobel-prizewinning Bengali Poet Rabindranath Tagore, "Golden Bengal":

. . . come Spring, O mother mine!

Your mango groves are heady with fragrance, The air intoxicates like wine.

Come autumn, O mother mine!

I see the honeyed smile of your harvest-laden fields.

It is indeed a land of unexpectedly lush and verdant beauty, whose emerald rice and jute fields stretching over the Ganges Delta as far as the eye can see belie the savage misfortunes that have befallen its people. The soil is so rich it sprouts vegetation at the drop of a seed, yet that has not prevented Bengal from becoming a festering wound of poverty. Nature can be as brutal as it is bountiful, lashing the land with vicious cyclones and flooding it annually with the spillover from the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers.

Improbable Wedding

Even in less troubled times, Pakistanis were prone to observe that the only bonds between the diverse and distant wings of their Moslem nation were the Islamic faith and Pakistan International Airlines. Sharing neither borders nor cultures, separated by 1,100 miles of Indian territory (see map), Pakistan is an improbable wedding of the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The tall, light-skinned Punjabis, Pathans, Baluchis and Sindhis of West Pakistan are descendants of the Aryans who swept into the subcontinent in the second millennium B.C. East Pakistan's slight, dark Bengalis are more closely related to the Dravidian people they subjugated. The Westerners, who eat wheat and meat, speak Urdu, which is written in Arabic but is a synthesis of Persian and Hindi. The Easterners eat rice and fish, and speak Bengali, a singsong language of Indo-Aryan origin.

The East also has a much larger Hindu minority than the West: 10 million out of a population of 78 million, compared with 800,000 Hindus out of a population of 58 million in the West. In Brit ish India days, the western reaches of what is now West Pakistan formed the frontier of the empire, and the British trained the energetic Punjabis and Pathans as soldiers. They scorn the lungi, a Southeast Asian-style sarong worn by the Bengalis. "In the East," a West Pakistani saying has it, "the men wear the skirts and the women the pants. In the West, things are as they should be."

Twenty Families

The West Pakistanis were also determined to "wear the pants" as far as running the country was concerned. Once, the Bengalis were proud to be long to Pakistan (an Urdu word meaning "land of the pure"). Like the Moslems from the West, they had been resentful of the dominance of the more numerous Hindus in India before partition. In 1940, Pakistan's founding fa ther, Mohammed AH Jinnah, called for a separate Islamic state. India hoped to prevent the split, but in self-determination elections in 1947, five predominantly Moslem provinces, including East Bengal, voted to break away. The result was a geographical curiosity and, as it sadly proved, a political absurdity.

Instead of bringing peace, independence and partition brought horrible massacres, with Hindus killing Moslems and Moslems killing Hindus. Shortly be fore his assassination in 1948, Mahatma Gandhi undertook what proved to be his last fast to halt the bloodshed. "All the quarrels of the Hindus and the Mohammedans," he said, "have arisen from each wanting to force the other to his view."

From the beginning, the East got the short end of the bargain in Pakistan. Though it has only one-sixth of the country's total land area, the East contains well over half the population (about 136 million), and in early years contributed as much as 70% of the foreign-exchange earnings. But West Pakistan regularly devours three-quarters of all foreign aid and 60% of export earnings. With the Punjabi-Pathan power elite in control for two decades, East Pakistan has been left a deprived agricultural backwater. Before the civil war, Bengalis held only 15% of government jobs and accounted for only 5% of the 275,000-man army. Twenty multimillionaire families, nearly all from the West, still control a shockingly disproportionate amount of the country's wealth (by an official study, two-thirds of the nation's industry and four-fifths of its banking and insurance assets). Per capita income is miserably low throughout Pakistan, but in the West ($48) it is more than half again that in the East ($30).

To cap this long line of grievances came the devastating cyclone that roared in off the Bay of Bengal last November, claiming some 500,000 lives. The callousness of West toward East was never more shockingly apparent. Yahya waited 13 days before visiting the disaster scene, which some observers described as "a second Hiroshima." The Pakistani navy never bothered to search for victims. Aid distribution was lethargic where it existed at all; tons of grain remained stockpiled in warehouses while Pakistani army helicopters sat on their pads in the West.

Supreme Sacrifice

It was something that Yahya had simply not anticipated. He and his fellow generals expected that Mujib would capture no more than 60% of the East Pakistani seats, and that smaller parties in the East would form a coalition with West Pakistani parties, leaving the real power in Islamabad. Mujib feared some sort of doublecross: "If the polls are frustrated," he declared in a statement that proved horribly prophetic, "the people of East Pakistan will owe it to the million who have died in the cyclone to make the supreme sacrifice of another million lives, if need be, so that we can live as a free people."

With the constitutional assembly scheduled to convene in March, Yahya began a covert troop buildup, flying soldiers dressed in civilian clothes to the East at night. Then he postponed the assembly, explaining that it could not meet until he could determine precisely how much power and autonomy Mujib wanted for the East. Mujib had not espoused full independence, but a loosened semblance of national unity under which each wing would control its own taxation, trade and foreign aid. To Yahya and the generals, that was unacceptable. On March 25, Yahya broke off the meetings he had been holding and flew back to Islamabad. Five hours later, soldiers using howitzers, tanks and rockets launched troop attacks in half a dozen sections of Dacca. The war was on. Swiftly, Yahya outlawed the Awami League and ordered the armed forces "to do their duty." Scores of Awami politicians were seized, including Mujib, who now awaits trial in remote Sahiwal, 125 miles southwest of Islamabad, on charges of treason; the trial, expected to begin in August, could lead to the death penalty.

Out of Touch

In the months since open conflict erupted, nothing has softened Yahya's stand. In fact, in the face of talk about protracted guerrilla fighting, mounting dangers of war with India, and an already enormous cost in human suffering, the general has only stiffened. Should India step up its aid to the guerrillas, he warned last week, "I shall declare a general war—and let the world take note of it." Should the countries that have been funneling $450 million a year in economic aid into Pakistan put on too much pressure, he also warned, he will do without it.

He has already lost some. After touring East Pakistan last month, a special World Bank mission recommended to its eleven-nation consortium that further aid be withheld pending a "political accommodation." World Bank President Robert McNamara classified the report on the grounds that it might worsen an already difficult diplomatic situation. The report spoke bluntly of widespread fear of the Pakistani army and devastation on a scale reminiscent of World War II. It described Kushtia, which was 90% destroyed, as "the My Lai of the West Pakistani army." A middle-level World Bank official leaked the study, and last week McNamara sent Yahya an apology; in his letter he reportedly said that he found the report "biased and provocative." Yet one Bank official insisted that though it was later revised and modified somewhat, its thrust remained the same. "We just had to put it on a less passionate basis," he said. "But it did not reduce its impact."

U.S. policy has been murky, to say the least. The Nixon Administration continues to oppose a complete cutoff of U.S. aid to Pakistan. The White House has asked Congress for $118 million in economic assistance for Pakistan for fiscal 1971-72, which it says will be held in abeyance. Despite intense pressure from within his official family, as well as from Congress. Nixon argues that a total cutoff might drive Pakistan closer to China, which has been one of its principal suppliers of military aid since 1965, and also destroy whatever leverage the U.S. has in the situation. In the light of Henry Kissinger's trip to China, however, it now seems clear that there may have been another motive for the Administration's soft-pedaling. Pakistan, of course, was Kissinger's secret bridge to China.

Nonetheless, criticism has been mounting, particularly in the Senate, with its abundance of Democratic presidential aspirants. Senator Edward M. Kennedy charged that the World Bank report, together with a State Department survey predicting a famine of appalling proportions, "made a mockery of the Administration's policy." Two weeks ago, the House Foreign Affairs Committee recommended cutting off both military and economic aid to Pakistan. The bill still must clear the House and the Senate, but its chances of passage are considered good.

Since 1952, when massive aid began, Pakistan has received $4.3 billion from the U.S. in economic assistance. In addition, the U.S. equipped and maintained the Pakistani armed forces up until 1965. Then, because of the Pakistani-Indian war, arms sales were dropped. Last October the Administration resumed military aid on a "onetime basis." After the East Pakistan conflict erupted, it was announced that arms shipments would be suspended; but when three ships were discovered to be carrying U.S. military equipment to Pakistan anyway, the State Department explained that it intended only to honor licenses already issued. Over the years, it is estimated that close to $1 billion has been provided for military assistance alone.

Condoning Genocide

India is particularly incensed over the present U.S. policy, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi strongly protested to Henry Kissinger about U.S. military shipments when he visited New Delhi this month. The supply of arms by any country to Pakistan, Foreign Minister Swaran Singh charged last week, "amounts to condonation of genocide." Mrs. Gandhi is faced both with mounting pressure for military action, and an awesome cost that could set her own economy back years. India is feeding the refugees for a mere 1.10 rupees (150) per person per day, but even that amounts to more than $1,000,000 a day. The first six months alone, Indian officials say, will cost $400 million. Contributions pledged by other countries (the U.S. leads with $73 million) equal barely one-third of that—and much of that money has not yet actually been paid.

Still, it would hardly be cheaper to launch a war and get it over with, as some high-level Indians openly suggest. Hours after Indian troops marched into East Pakistan, Pakistani tanks and troops could be expected to roll over India's western borders. Moreover, fighting could spread over the entire subcontinent. For all of India's commitment "to Bangla Desh democracy and those who are fighting for their rights," in the words of Mrs. Gandhi, New Delhi is not at all interested in taking on the burden of East Bengal's economic problems. The only answer, as New Delhi sees it, is a political solution that would enable refugees to return to their homes.

The impetus for that could conceivably come from West Pakistanis. It is still far from certain that they are really determined to go the distance in a prolonged war. Thus far, the war has been officially misrepresented to the people of the West as a mere "operation" against "miscreants." Tight censorship allows no foreign publications containing stories about the conflict to enter the country. Even so, as more and more soldiers return home badly maimed, and as young officers are brought back in coffins (enlisted men are buried in the East), opposition could mount. The pinch is already being felt economically, and there have been massive layoffs in industries unable to obtain raw materials for lack of foreign exchange.

Immense Suffering

Meanwhile, the food supply in East Pakistan dwindles, and there is no prospect that enough will be harvested or imported to avert mass starvation. August is normally a big harvest month, but untold acres went unplanted in April, when the fighting was at its height. Already, peasants along the rainswept roads show the gaunt faces, vacant stares, pencil limbs and distended stomachs of malnutrition. Millions of Bengalis have begun roaming the countryside in quest of food. In some hard-hit locales, people have been seen eating roots and dogs. The threat of starvation will drive many more into India. Unless a relief program of heroic proportions is quickly launched, countless millions may die in the next few months. Yahya's regime is not about to sponsor such an effort. His latest federal budget, adopted last week, allocates $6 out of every $10 to the West, not the East; in fact, the level of funds for Bengal is the lowest in five years. The U.S., still fretful about driving Yahya deeper into Peking's embrace, seems unlikely to provide the impetus for such a program.

Tagore once wrote:

Man's body is so small, His strength of suffering so immense.

But in golden Bengal how much strength can man summon before the small body is crushed?