|

| Photo: |

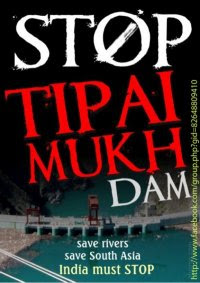

Conflicts without a media-friendly visual are neglected by the world stage, observes.

1971. Journalists accompanied a post-Chappaquidick Edward Kennedy into refugee camps. Lear Levin's camera followed a singing troupe across the border, capturing footage that would be rediscovered by Tareque Masud. Bill Moyer designed a media-attuned blockade of US ships. Joan Baez and George Harrison both had chart-topping singles with the name of this new country (with an extra space in between). Finally, the Concert for Bangladesh became the blueprint for future mega-events like Live Aid.

Already mobilised by the Vietnam war, the zeitgeist of the global peace movement shifted logically to supporting new causes, including the Bengali movement. In Europe and North America, people were already on the streets -- angry, energised and distrustful of governments. This evolved into concern for other troubled spots, and potential superpower involvement focused people's interest further. Whether universal analyses exactly fit each situation was somewhat beside the point, the urge was to move into action.

Underpinning this increasing awareness of new countries and conflicts was the expanding role of photography and film -- as witness and advocate. Television had already embraced a more primary role during the Vietnam war. When America's most trusted television newsreader Walter Cronkite journeyed into the war zone, everything shifted. On his return to America, Cronkite presented the report "Who, What, When, Where, Why" on CBS Evening News (February 27, 1968) -- a devastating critique of the war effort. The impact of this one television broadcast was seismic. A few weeks later, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced he would not seek re-election.

The stories of Vietnam that decisively demonstrated to the country that it was an unwinnable war were often broken through graphic images: from the My Lai massacre to the over-run Marine base at Khe Sanh. Slowly there also emerged film, alongside each photo sequence. The brutal execution of a captured Vietcong soldier was captured by both photographer Eddie Adams (AP) and cameraman Vo Su (NBC)1. Adams' photographs, minus the crucial moment of the blood-spurting head, had an eerie film strip look. Back in the US, the press ran his entire sequence of photographs, further eroding support for the war.

The 1971 genocide in Bangladesh, as well as other conflicts in that period, played out in a Vietnam war context of increased availability of the image to accompany text, and even text in a hyper-visualised form (starting to mimic the photo that was sometimes its companion, sometimes competition).

Reporters as advocates

George Washington Williams, a freed American slave, was the first investigator to expose King Leopold's Congo. Williams' 1890 Open Letter was a comprehensive, documented charge that the Belgian colonial regime was engaged in torture, “wholesale and retail” slavery, kidnapping and concubinage.2 This was followed by an open letter to the US President urging American action. But when newspapers like the New York Herald ran the story, they gave equal weight to the Belgian denials. Leopold's advisers were very concerned by "un vrai scandale" of "le pamphlet Williams." But they found it easy to insinuate that Williams could not be trusted because, as a Black man writing about Africa, he had inherent sympathies. Congo administrators were able to repeatedly caricature him as "an unbalanced negro." The issue did not fully catch the world's attention, because the messenger was easy to dismiss due to racial coding.

A decade after Williams, E. D. Morel, an employee of an English shipping line doing business in Congo, stumbled onto the mechanics of Leopold's empire. A quiet shipping clerk who paid attention to bookkeeping records, Morel discovered massive amounts of arms being shipped to the Congo off the record. He also analysed the discrepancy between imported goods and exported rubber and ivory and realised the Belgian state was not paying anyone for these materials. This led him to the conclusion that, hidden from the public eye, King Leopold was running the colonial state with thousands of natives working as slaves to extract raw materials and plunder the nation, while pretending to the outside world that Belgium and the Congo were engaged in a mutually beneficial trading partnership. Describing this discovery, Adam Hochschild wrote, "It was as if, in 1942 or 1943, somebody who began to wonder what was happening to the Jews had taken a job inside the headquarters of the Nazi railway system."3

Morel was a very different witness from Williams. With access to the sympathy of white readers, he could not as easily be debunked. He resigned his commission and began writing for British newspapers. Finding his Congo articles censored, he resigned and started his own publication in 1903, The West African Mail. Besides editing the newspaper, and writing under his own name, he also took on an African identity and wrote as "Africanus." He went on to write three full books and segments of two others, hundreds of articles for British newspapers, articles in French for Belgian and French newspapers, hundreds of letters and dozens of pamphlets. This reporting ultimately forced passage of the Congo protest resolution in British Parliament in 1903. This was the beginning of the stirring of a global campaign, which would ultimately force an end to Leopold's rule over Congo. As a white employee of British shipping, Morel eased into a racial context that gave his testimony “weight,” altering the history of the Congo.

In 1971, the factors deciding impact and audience were not necessarily the race, but rather the position of the reporter within the context of other proxy battles being fought on their home turf. There were Indian journalists covering this story, who did not receive global or unitary attention. Among Pakistani journalists, Anthony Mascarenhas was the first to charge that the Pakistan army was engaged in ethnic and religious cleansing. As a Christian from Pakistan, he knew that the West Pakistani institutions would find many reasons to question his loyalty and would arrest him (as happened with other dissenting Pakistanis). Therefore, he escaped to London, and then ran his front-page article for the London Sunday Times, which carried the first use of the term “genocide” to describe the war. Speaking of how Asian journalists were frozen out of the inner circles, Mascarenhas commented: "I had been too long a journalist not to know that a relative "outsider" such as I was, even with the biggest story in the world, could be indefinitely knocking on the doors of Fleet Street."4

Among the reporters covering Bangladesh from the west, especially prominent were Amold Zeitlin (Associated Press), Peter Kann (Wall Street Journal, Pulitzer winner in 1972 for his war reporting), Sidney Schanberg (New York Times), Tad Szulc (New York Times), John Chancellor (NBC News), and Jack Anderson (Washington Post, Pulitzer winner in 1972 for his war reporting) among others. The leaking of Vietnam archives (known as The Pentagon Papers) to the New York Times had created a confrontational dynamic between journalists and the Nixon White House. Anderson followed this by divulging official secrets regarding Bangladesh, in what was later called The Anderson Papers. In December 1971, Anderson discovered a disconnect between public White House statements and private meetings. On December 6, President Nixon informed leaders of Congressional groups that the Administration planned to be "even handed"5 in the dispute. But according to secret memos obtained by Anderson, in a meeting on December 3rd, Henry Kissinger said the opposite.6

In another memo obtained by Anderson, Kissinger said, "When is the next turn of the screw against India?" He also asked if the United States could ship arms to Pakistan via Saudi Arabia or Jordan. More damaging for Nixon was the revelation that he had secretly ordered the nuclear-operated Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal to confront Indian forces. The Enterprise was headed off by a Russian frigate and, after a tense standoff, both sides retreated, leaving the Indians and Pakistanis to fight out the war. Anderson publicly blasted Nixon over his handling of the Bangladesh crisis: "It was deliberate and it was in violation of the US Constitution."7 He ended up winning a 1972 Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the secret meetings.

Through public battles between Nixon and the Fourth Estate, we saw the emergence of crusading American journalists like Anderson -- people who had the power to decisively alter the attention being paid to a far-away conflict, specifically by linking it to domestic debates about Presidential power that were already at peak inside the United States.

|

| Photo: |

Who's it between?

"Oh those unspeakable Serbs! And then there are the envious Hutus and the arrogant Tutsis, not to mention the aggressive Dinka. Consider how many groups of people and cultures about whom -- until they were recently engaged in bloody civil wars -- you knew little -- but of whom you now have a clear, despairing, view."8 -- Jean Seaton

As television came to dominate news reporting, the hyper visual changed the rules of conflict journalism. Complex situations, with multiple causes, linkages to colonial structures and hazy outcomes were flattened (even more than in the print-only era) to what David Keen ironically describes as, "Who's it between?"9 There is a desire to reduce conflicts between ethnic groups to "ancient barbarism", or the infamous "from time immemorial" explanation for the Bosnian conflict. This is explained by a theory of primordialism, as reflected in British coverage of Bosnia: "They were driven by that atavistic fury that goes back to the times when human beings moved in packs and ate raw meat."10

This primordialism hypothesis plays out especially in media coverage of African conflicts, infected by a streak of "afropessimism" -- where the continent is a “savage land” that descends to bestiality at the slightest provocation, with no agency assigned to its colonial history. African political cliques also play into this, because these theories help them to escape censure. The Rwandan conflict is an example where complex political machinations laid the groundwork for ethnic cleansing. But all this was deleted in favour of the story of "ancient hatred" between Tutus and Hutsis. The use of machetes ("Although the killing was low tech -- performed largely by machete -- it was carried out at dazzling speed")11 played into the notion of pre-technology people.

Similar simplifying structures were used to paint a clear narrative of the 1971 conflict and mobilise international support for the victims. Lost in this process were the complexities of the struggle, including the conflicting political strands within the Bengali liberation movement. The democracy movement, as it erupted in Pakistan in the 1960s, had several overlapping aspects. First, there was the strongly class antagonistic, workers vs. business overtone of the struggle. Second, there was the potential for the movement to become a pan-Pakistan struggle, as the West Pakistani students and unions were equally dissatisfied as was East Pakistan with the newly industrialising economy (although for very different structural reasons). These trajectories were radically shifted by the landslide victory of the Awami League (AL) in the 1970 Pakistan elections. The AL was led by a rising Bengali middle class and emerging business elite.

This leadership had an unstable relationship with the ultra-left ideology of some sectors of student, which accelerated after 1971. When the war broke out, these tensions manifested themselves, especially as the Bengali guerilla army set up headquarters in India. The Indian government was continuously concerned about any militant left tendencies (broadly defined) within the Bengali movement, and the possibility of linkages with the Naxalites in India. This anxiety was projected into the League's leadership as well. But in the media treatment of 1971, these complexities were erased. In its place, there was the story of the bucolic Bengali people, pitted against an urbanised Pakistani state and military. Anthony Mascarenhas played into this: "In West Pakistan, nature has fostered energetic, aggressive people -- hardy hill men and tribal farmers who have constantly to strive for a livelihood in relatively harsh conditions. They are a world apart from the gentle, dignified Bengalis who are accustomed to the easy abundance of their delta homeland in the east."12 Much of this framing, including the specific language Mascarenhas used, was rooted in colonial history, especially the British Raj's decision to raise “native” army battalions along racial lines, with a focus on the “martial races”13 and benign neglect of the “clerical” class and rural forces.

Salman Rushdie replayed these constructs in his novel Shame, satirising the Pakistani attitude towards Bengalis: "Savages, breeding endlessly, jungle-bunnies good for nothing but growing jute and rice, knifing each other, cultivating traitors in their paddies." Later, in 1971, there arrived "the appalling notion of surrendering the government to a party of swamp aborigines, little dark men with their unpronounceable language of distorted vowels and slurred consonants; perhaps not foreigners exactly, but aliens without a doubt."14

The concept of "gentle" people came in spite of a long history of revolutionary movements. During the anti-British movement, a segment of the Bengali peoples preferred to arm themselves with western weapons and carry out a militant struggle. This included the 1930 Chittagong armory raid (inspired by the Dublin Easter Uprising) and Subhas Bose's Indian National Army. In fact, the technology-rejecting programme of Gandhi offered some comfort to the British, while Bose, who believed in fighting the British with modern weapons, was a more unsettling, radical force.

Therefore, the Bengalis in 1971 could also have been framed as carrying on that lineage of armed struggle. As we have seen often, a provable direct linkage is not necessary for journalists to construct a headline. But instead, the western media preferred to portray Bengalis as helpless masses with little recourse to self-defense, except toward the end when there was more concerted press coverage of the Mukti Bahini. Although the Bengali liberation forces were clearly outgunned by a well-armed, state-supported Pakistani army, the portrait of "gentle, rice-eating people" obscured some of the complexities.

For the purposes of a television-friendly story, the narrative structure had to be reduced to striking visual images. The photo of a Bengali woman being carried by her husband, and the crippled refugee hobbling through mud toward India, represented the Bengali crisis in totality. The nature of photography and film also added a prism of artificiality. The shirtless peasant walking wearily to refugee camps was often captured in verite moments, but the images of soldiers preparing for battle, or in battle, were invariably in a safe zone (more for the photographer's safety) and therefore had a visible element of staging. There is no doubt that there were thousands of moments of intense fighting, whether by the Bengali peasant who became cannon fodder, or the middle class revolutionary who carried out urban sorties, but the camera was often not there in that moment.

News cycle

By 1970, a proliferation of American TV channels, competing broadcasts and industry pressure, led to the pursuit of news calibrated to appeal to a mass audience tuning in for event viewing at 8 or 9 pm each night. Therefore, in order to appeal to an increasingly mechanised news gathering process, it was necessary to pursue big media events.

A group of American activists called Friends of East Bengal (FEB) found this changed news media increasingly blasé about normal street protests. In response, they implemented street theatre about Bangladesh to get camera attention. Richard Taylor, who had worked with Martin Luther King, adopted this model of theatre from the civil rights movement. Bill Moyer of FEB led the decision to mount blockades of ships carrying US arms to Pakistan, using little boats and canoes: "Like civil rights sit-ins, it was dramatic, direct and nonviolent."15 Starting in July 1971, this team began a sustained campaign of tracking down the Pakistani ships Padma, Al Ahmadi, Al Hasan and Rangamati. As each of these ships would try to dock at Philadelphia or Baltimore, the FEB would head out with their flotilla of small boats to block entry. Each trip was taken after first contacting TV, radio and newspapers and ensuring their timely arrival. The results were measured by whether newspaper reports carried photos, and whether the TV news carried film of the event. Bill Moyer particularly focused on TV news, sometimes delaying actions until reporters arrived.

As this action spread out across weeks, a cat and mouse game ensued between the shipping lines and protesters. Increasingly the ships would change course and not arrive. Soon, the authorities started getting orders not to reveal docking information. A Philadelphia Maritime Exchange officer confessed to one of the activists: "We've been instructed not to make public any information on ships to Pakistan. We're not supposed to put them on the big board or to list them in the Journal of Commerce." The pursuit of the ships became the news item itself. Each time the blockade would show up at a dock and not find the ship, the news media would be told the ships were afraid to dock. In these matters, the protesters showed themselves adept at managing media impatience. The changing dynamic of direct action was reflected in this confrontation: "One reporter angrily confronted Bill Moyer: 'You got us here on a wild goose chase. The boat's not here.' Bill smiled: 'I guess you don't know a successful blockade when you see one. The ship is afraid to come in. We're claiming success and we're going to continue.'"

Many of the activists of FEB were white. The few Bengalis in visible positions were sometimes stand-ins for romanticised conceits. Monayem Chowdhury, the Bengali male in the group, was described as "short, soft-spoken, Gandhi-like" and Sultana Krippendorf was in "flowing sari, petite figure, long black hair, lovely dark skin, and large brown eyes". Elsewhere she was a "lovely woman with foreign accent." Television cameras also picked up these visual cues in their filming. Richard Taylor was the unofficial biographer of the blockade movement, and in his descriptions we also see a desire to counter the reputation in the US mainstream of anti-war protesters as “unAmerican”. In his book, he talks of the "all-American" makeup of the participants. In Taylor's description, Alex Cox was a " red haired Texan," Jack Patterson a "tall, slim, mustached, thirty-two year-old," and Wayne Lauser was "tall, with a head band," On the other side, Patrolman Walter Roberts, who showed sympathy to the demonstrators, was described as "friendly, open face, with hazel eyes and close cropped blond hair."

Because television carried nightly broadcasts of the blockade action, newspapers also followed, afraid of being left behind by the newer media. The power dynamic had shifted -- television was the action, and the protesters now calibrated their activities based on which images were ideal for moving film. Bill Moyer told a planning meeting: "I can pass out hundreds of thousands of leaflets and still not reach anything like the audience Walter Cronkite reaches every night." After all, Cronkite had contributed to President's Johnson's collapse. It was time for the full realisation of a television war.

Syed Arif Yousuf, who is working on Blockade, a documentary about FEB, provides a framing for all this: “We should never think they were single-mindedly looking for media attention. I found them passionately believing in the cause and trying to do something about it. Media was the path to that.”16

Faster media

As tools get smaller and faster, the cycle of news-gathering accelerates. During the Congo genocide, the gap between news gathering and publication was often months. George Washington Williams' open letter to King Leopold, subsequent open letter to the US President, publication as a pamphlet, citation in the New York Herald, translation in French press and eventual rebuttal in Journal de Bruxelles -- each of these milestones occurred with gaps of several months. Between Williams' initial report, and E.D. Morel's next investigation, there is a gap of 10 years. In totality the media coverage of the Congo crisis extended over many decades. In contrast, today there is an incredible velocity in media mechanisms, which would be unthinkable to the slow reporting and advocacy of Morel's time.

The shifting speed of media can be shown through a simple comparison between two years. In 1994, when an earthquake hit Los Angeles, it took 40 minutes for the news to reach President Clinton, via HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros who was sitting in CBS television studios. In contrast, a year later, when the Kobe earthquake happened, University students -- the earliest users with access to Internet networks -- started spreading word of the earthquake before the tremors had even faded. "The ground was still shaking when university students began firing up their computers to spread word of the disaster."17

As speed takes over, the focus is on "hot news" and viewers also get tired of stories much faster. This pattern of media exhaustion was already starting as far back as 1971. In the rush to move on to the next war zone, the media blanked out on many of the developments inside Bangladesh during and after 1971. By 1975, very few western outlets followed the aftermath of Sheikh Mujib's assassination. It is noticable that news reports of events in the 1970s, including Sheikh Mujib's assassination, were often not accompanied by very many multi-camera moving images. This was not just due to the coup-plotters' media blackout, but also because fewer journalists were covering the country. The hot zone had moved elsewhere. So complete is the departure of interest that 1971 is now described in many reports as the "Third India-Pakistan war." A conflict between the Bengalis and the state of Pakistan is forced into a footnote in the story of Indo-Pak tensions and "enduring enmity over Kashmir".

The Bangladesh war and genocide is both representative and atypical of media-led globalised conflict coverage. It is representative because of the issues regarding elimination of complexity, reliable narrators, news cycles and racial coding. But it is atypical because certain factors converged to keep the media attention focused longer than it would have otherwise.

The proliferation of the visual has led to a perpetual need for events and media stunts to gain attention. Conflicts without a media-friendly visual are neglected by the world stage. An accelerated media cycle means that "hot news" also becomes cold. Conflicts that last for longer periods (e.g., Sri Lanka) are often left behind.

Even when there is coverage, something, somewhere feels wrong. There can be dozens of cameras, of every imaginable size and capacity, recording the site of new catastrophes. Yet we gaze at images that tell us little, sometimes (not always, of course) fulfilling a voyeuristic desire, without a call to action or responsibility. All our evolved, inexpensive, miniaturised technologies have sometimes led to a dehumanisation of the news cycle and of reporters. It is crucial to find ways to use all of the advanced technologies in media, without losing our original humanity and ability to bear witness in a slow, thoughtful manner.

In memory of Tareque Masud and Mishuk Munier.

1. A knowing homage to this moment can be seen in the point-blank execution of a Kurdish woman in David O. Russell's film Three Kings, an example of trenchant political analysis disguised as a popcorn blockbuster.

2. Adam Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost, Mariner Books, 1998, p.\111.

3. Hoschchild, p 177

4. Anthony Mascarenhas, The Rape of Bangla Desh, Vikas, 1971, p. iv

5. Vinod Gupta, Anderson Papers: A Study of Nixon's Blackmail of India, ISSD Publications, 1972

6. Memo to Assistant Secretary of Defense (3 December 1971), quoted by Gupta, p 97

7. Anderson, speaking to Inland Daily Press Association Convention, February 29, 1972, quoted by Gupta, p 44.

8. Jean Seaton, "The New Ethnic Wars and the Media", The Media of Conflict, Tim Allen, Jean Seaton, Ed., Zed Books, 1999.

9. David Keen, "Who's It Between? Ethnic War and Rational Violence", The Media of Conflict, Tim Allen, Jean Seaton, Ed., Zed Books, 1999.

10. Guardian, 25 April, 1998

11. Philip Gourevitch, We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Picador, 1998.

12. Mascarenhas, p 10.

13 Rand, Gavin. "Martial Races and Imperial Subjects: Violence and Governance in Colonial India 18571914". European Review of. History (Routledge) 13 (1), March 2006: 120.

14. Salman Rushdie, Shame, Jonathan Cape, 1983, p 195.

15 Richard Taylor, Blockade, Orbis Books, p 7.

16. Author interview, August 16, 2011.

17 John M. Moran, "Internet Becomes Quake-Net," Hartford Courant (January 20, 1995), A1.

BY : NAEEM MOHAIEMEN.